Why is it called epidemiology?

The term “Epidemiology” can be referred to as “the study of the distribution and determinants of health-related states or events in specified populations, and the application of this study to control of health problems”. This focuses attention that epidemiologists are concerned not only with illness, death, and disability but also with more positive health states and with the means to better the health of a large population, not only individuals.

The motive of a study in epidemiology is usually a wide human population. A population can be defined in geographical or other terms for example, a specific group of ill patients or factory workers could be the unit of an epidemiology study. A common population used in epidemiology is one in a specific area or country at a given time. This forms the base for a certain subgroup to age group, sex, ethnicity, and so on.

The historical context of epidemiology

Epidemiology has its roots in the idea, first told over 2000 years ago by Hippocrates and others, that environmental factors can affect the occurrence of disease. However, it was not until the nineteenth century that the dispersal of disease in specific human population groups was measured to a great extent. This work marked not only the formal start of epidemiology but also some of its most stunning achievements.

For example, the finding by John Snow that the risk of cholera in London was described, among other things, as the drinking of water supplied by a particular company. Snow’s epidemiological studies were one element of a wide-ranging series of investigations that entangled an examination of chemical physical, biological, sociological, and political procedures (Cameron & Jones, 1983).

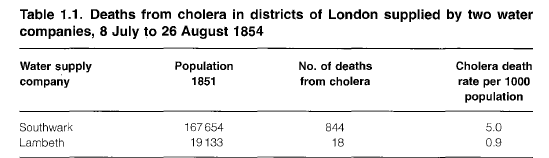

Snow located the home of each person who passed away from cholera in London during 1848-49 and 1853-54 and noted a prominent association between the source of drinking water and the deaths. He prepared a statistical comparison of cholera deaths in districts with distinct water supplies (Table 1.1) and thereby showed that both the number of deaths and, more notably, the mortality rate were high among people provided by the Southwark company. Based on his detailed research

Snow created a theory about the transmission of infectious diseases in general and proposed that cholera was spread by polluted water. He was thus able to promote advancements in the water supply long before the discovery of the organism accountable for cholera his research had an immediate impact on public policy.

Snow’s work reminds us that public health efforts, such as the improvement of water supplies and sanitation, have made tremendous contributions to the health of populations. In many cases since 1850 epidemiological studies have shown the appropriate measures to take.

The epidemiological strategy of comparing rates of disease in subgroups of the human population evolved increasingly used in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Question:- Who is the father of epidemiology?

Answer –John Snow, considered to be the father of epidemiology

Uses of epidemiology

Epidemiology is commonly used to identify the health status of specific population groups. Knowledge of the disease burden in populations is very necessary for health authorities, which try to find lesser resources to the best possible effect by identifying priority health programs for prevention and care.

In some specialist areas, such as environmental and occupational epidemiology, the focus is on studies of populations with specific types of environmental exposure. Epidemiology has upgraded considerably over the past 50 years and the main challenge now is to explore and implement the social determinants of health and disease.

Recently, epidemiologists have become involved in the analysis of the effectiveness and efficiency of health services, by determining the sufficient length of stay in hospital for specific conditions, the value of treating high blood pressure, HDL Cholesterol, LLD Cholesterol, the efficiency of sanitation measures to control diarrhoeal diseases, the impact on public health of decrease the lead additives in petrol, and so on.

What is an example of epidemiology?

- Case-control studies: The degree of connection between various risk factors and outcomes is used in case-control studies.

- Cohort studies differentiate patients into two groups. It checks if the patient forms the disease in the exposed or unexposed groups.

- Experimental studies include randomized clinical tests that are standards for study purposes.

Causation in epidemiology

The main motive of epidemiology is to assist and identify the prevention and control of disease. The promotion of health by searching the causes of disease and the ways in which they can be modified.

the identification of the causes of disease is very important in the health field not only for prevention the of diseases but also for diagnosis and the application of adequate treatments. The study of causes is the source of much controversy in epidemiology, as it is in other sciences.

The philosophy of science continues to make contributions to the understanding of the process by which causal inferences, i.e. judgments linking postulated causes and their consequences, are made. The concept of cause has different meanings in different contexts and no definition is equally appropriate in all sciences.

The cause of a disease is a condition, event, characteristic, or a combination of these factors that plays a major role in producing the epidemiology disease. Logically, a cause must precede a disease. A cause is termed sufficient when it inevitably generates or initiates a disease and is termed necessary if a disease cannot develop in its absence.

A sufficient cause is not a single factor but often a composition of several components.

In general, it is not necessary to identify all the components of a sufficient cause before adequate prevention can take place, since the removal of one segment may interfere with the action of the others and thus control the disease. For example, cigarette smoking is one component of the acceptable cause of lung cancer.

Smoking is not adequate in itself to produce the disease: some people smoke for 50 years without developing lung cancer; other factors, mostly unknown, are required. However, the termination of smoking decreases the number of cases of lung cancer in a population even if the other component causes are not modified.

Each sufficient cause has a critical cause as a component. For example, in a

study of an outburst of foodborne infection, it may be discovered that chicken salad

and creamy desserts were both sufficient reasons for salmonella diarrhea. The

happening of salmonellae is a necessary cause of this disease. Similarly, there

are different parts in the causation of tuberculosis, but the tubercle bacillus

is a necessary cause as mentioned image below. A causal aspect on its own is often neither

necessary nor sufficient, e.g. smoking is an aspect in causing a stroke.

Factors in causation

- Predisposing factors such as age, sex, and previous disease, may create a state of vulnerability to a disease agent.

- Enabling factors such as low earnings, poor nutrition, bad housing, and insufficient medical care may favor the development of disease. Contrarily, occurrences that aid in recovery from illness or the maintenance of good health could also be called allowing factors.

- Precipitating factors such as openness to a specific disease agent or noxious agent may be associated with the onset of a disease or state.

- Reinforcing factors such as recounted exposure and unduly hard work may aggravate a designated disease or state.

Prevention of Epidemiology

The scope of prevention

The decrease in death rates that occurred during the nineteenth century in the United Kingdom was principally due to a decline in deaths from infectious diseases. The same system decline is now being seen in many growing countries, mainly as a result of general progress in standards of living, particularly in nutrition and sanitation. Significant control of certain diseases has been executed through specific preventive measures (for example, immunization against poliomyelitis), but in general, the role of distinct medical therapies has been less important.

Levels of prevention

Four levels of prevention can be identified, corresponding to different phases in

the evolution of disease as below picture

- primordial

- primary

- secondary

- tertiary

- Quaternary Prevention

All are important and complementary, although primordial prevention and

primary prevention has the most to donate to the health and well-being of

the whole population

Primordial Prevention

In 1978, the numerous recent addition to preventive procedures, primordial prevention, was described. It consists of risk factors decreasetargeted towards an entire population through a focus on social and environmental conditions. Such actions typically get promoted through laws and national policy. Because primordial precluding is the earliest prevention modality, it is often aimed at children to reduce as much risk exposure as possible. Primordial prevention targets the underlying stage of natural illness by targeting the underlying social conditions that promote disease onset. An example includes improving access to an urban surrounding to safe sidewalks to promote physical activity; this, in turn, declines risk factors for obesity, cardiovascular diseases, Cholesterol, type 2 diabetes, etc

Primary Prevention

Primary prevention consists of efforts aimed at a susceptible population or person. The purpose of primary precluding is to prevent a disease from ever happening. Thus, its target population is healthy individuals. It generally institutes activities that limit risk exposure or increase the immunity of someone at risk to prevent a disease from progressing in a susceptible individual to subclinical disease. For example, immunizations are a form of prior prevention.

Secondary Prevention

Secondary prevention highlights early disease detection, and its target is healthy-appearing individuals with subclinical forms of the disease. The subclinical illness consists of pathologic changes but no overt signs that are diagnosable in a doctor’s visit. Secondary prevention often appears in the form of screenings. For example, a Papanicolaou (Pap) smear is a form of secondary prevention desired to diagnose cervical cancer in its subclinical form before progression.

Tertiary Prevention

Tertiary prevention marks both the clinical and outcome stages of a disease. It is implemented in symptomatic patients and aims to reduce the harshness of the disease as well as any associated sequelae. While secondary prevention seeks to avert the onset of illness, tertiary prevention aims to reduce the effects of the disease once found in an individual. Forms of tertiary prevention are commonly restoration efforts.

Quaternary Prevention

According to the Wonca International Dictionary for General/Family Practice, quaternary precluding is “action brought to recognize patients at risk of overmedicalization, to protect them from new medical invasion, and to propose to them interventions, which are ethically acceptable.” Marc Jamoulle originally proposed this concept, and the targets were mainly patients with illness but without illness. The definition has experienced recent modification as “an action taken to protect someone (persons/patients) from medical interventions that are likely to cause more harm than good